The Simulation Engine

Mathematical and computational approaches to the dynamics of an infectious disease have a long history. Models first described by Kermack and McKendrick describe the how fractions of susceptible (S), infectious (I) and recovered (R) individuals of a population change over time. The dynamics of S, I and R are prescribed through coupled non-linear ordinary differential equations. Compartmental models ignore all variation at the individual level, and also assume that the population is well-mixed. Such models neglect complications associated with spatial variations in incidence and elide the interplay of social factors, such as family sizes, community networks and socio-economic status on disease dynamics.

Beyond compartmental models, network and agent-based (equivalently individual-based) approaches implement individual-level granularity. Realistic networks describing the interactions between people can contain a few highly connected nodes. Targeting such nodes, “super-spreaders” in the context of infectious disease dynamics, can have an overwhelmingly large effect compared to interventions that treat all nodes equivalently. Both network and agent-based models require many more assumptions, especially regarding the nature of contacts that lead to infection. However, they provide a more detailed way of understanding disease dynamics than is possible through compartmental models. They can thus also be used to assess the effects of targeted interventions, such as lock-downs and restrictions on public transport, in a more precise way.

A number of agent-based models have been used to study disease dynamics. There are relatively few such models for India. One, the IISc-TIFR city-based simulator, has been used to model COVID-19 spread in the major Indian cities of Bengaluru and Mumbai. Results from these models include the evaluation of strategies for reopening public transport in the background of an epidemic at different stages of its trajectory as well as studies of the impact of lock-downs and related interventions.

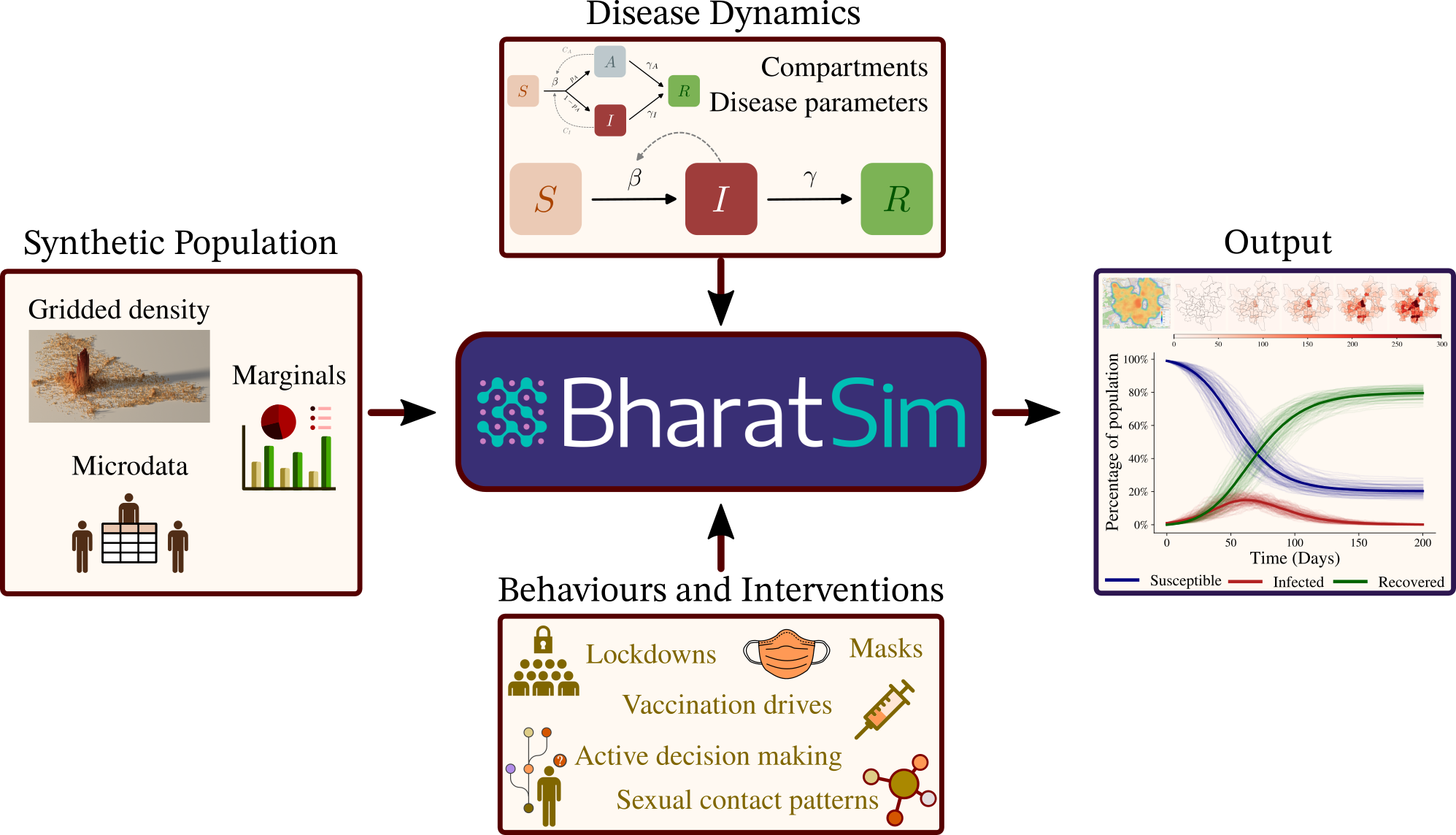

The agent-based simulation framework described here, BharatSim, defines and uses a more detailed description of the population than those in earlier work. Additionally, BharatSim is a framework, i.e. it provides a mechanism for users to address specific requirements easily instead of being forced to modify a large, existing base of code. While applications are designed to respond to a specific question, a simulation framework is more general. The simulation framework thus insulates the user from unnecessary implementation details, while providing them with sufficient flexibility.

BharatSim defines and uses a synthetic population that is a detailed and granular description of the population that is also statistically faithful. The simulation engine accepts this population as a CSV file. Additionally, the engine was designed so that it would be able to scale up to large population sizes without significant overhead or degradation in speed, given that one use of BharatSim would be to simulate populations of the size of an average Indian state, which also required the framework to implement efficient data structures and algorithms. Finally, we intended that BharatSim be usable on a range of conventionally available hardware ranging from personal laptops to High Performance Computing (HPC) clusters. Flexibility was another design imperative: we wanted modellers from a range of backgrounds, perhaps even lacking significant programming experience, to be able to easily define a new model and add further levels of abstraction, thus extending the framework in new ways.

Structure of the simulation engine

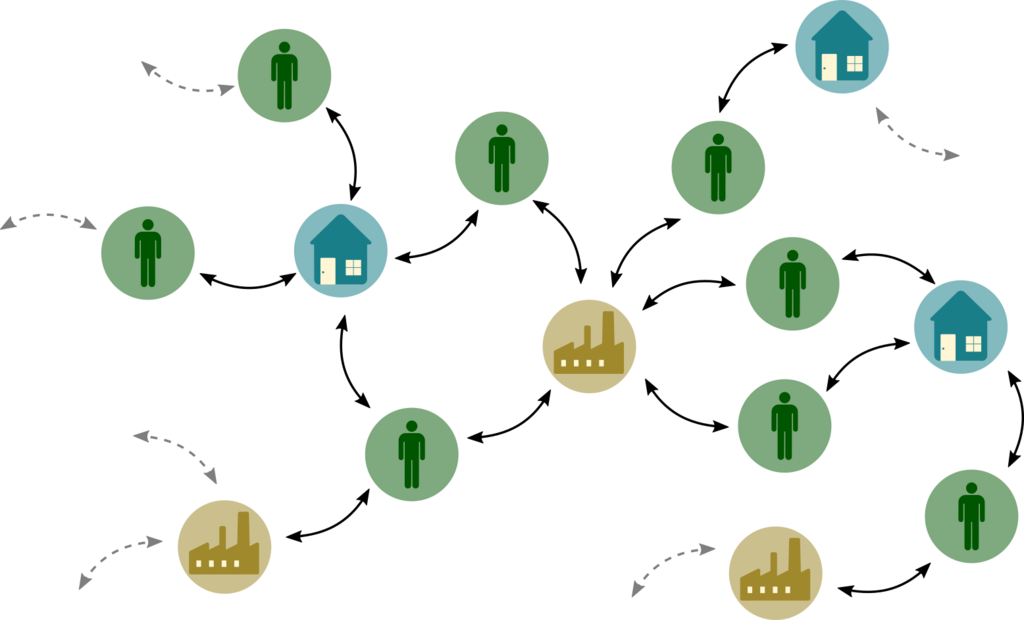

All data in the simulation engine is stored in a Graph. This graph is a network of nodes which can

represent both individual agents as well as locations such as households or offices. The framework defines a

Node class which allows for relations to be established between other such nodes. The Node

class is further extended to define the Agent and Network classes. The Network

classes can then be further extended to define specific locations like a Home or a Workplace

class.

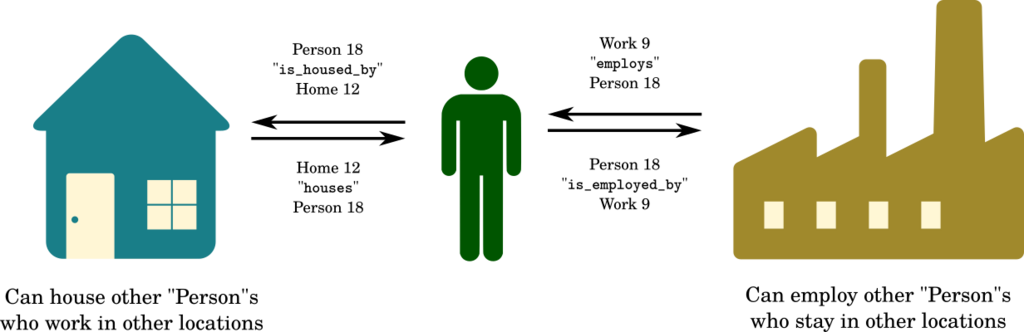

Thus, a typical graph might be one that's shown in the figure above: individual agents (extensions of the

Person class) are connected to Homes and Workplaces (both extensions of the Network class).

One could then establish relations between these nodes. For example, every Agent could be a resident of a specific

house (specified by a household id HHID) and be employed by a specific workplace (specified by the

WorkplaceID). The relations are bidirectional, and require one to additionally specify that the home

houses (and the workplace employs) that particular Agent (specified by the AgentID).

Using an abstraction like a graph makes the framework domain independent and flexible. This graph can be implemented in one of two ways, either by using Neo4j, a graph database, or using the Scala programming language's scalable map implementation TrieMap. The modeller can choose either of these implementations. Both these structures were chosen since they optimised data operations, allowing the simulation to scale efficiently to larger populations. The simulation engine framework allows modellers to directly specify their models using its own language. This domain-specific language is itself based on Scala, the language that the simulation framework has been written in. This allows modellers to extend their knowledge of Scala when creating their models.

The Agent and StatefulAgent classes

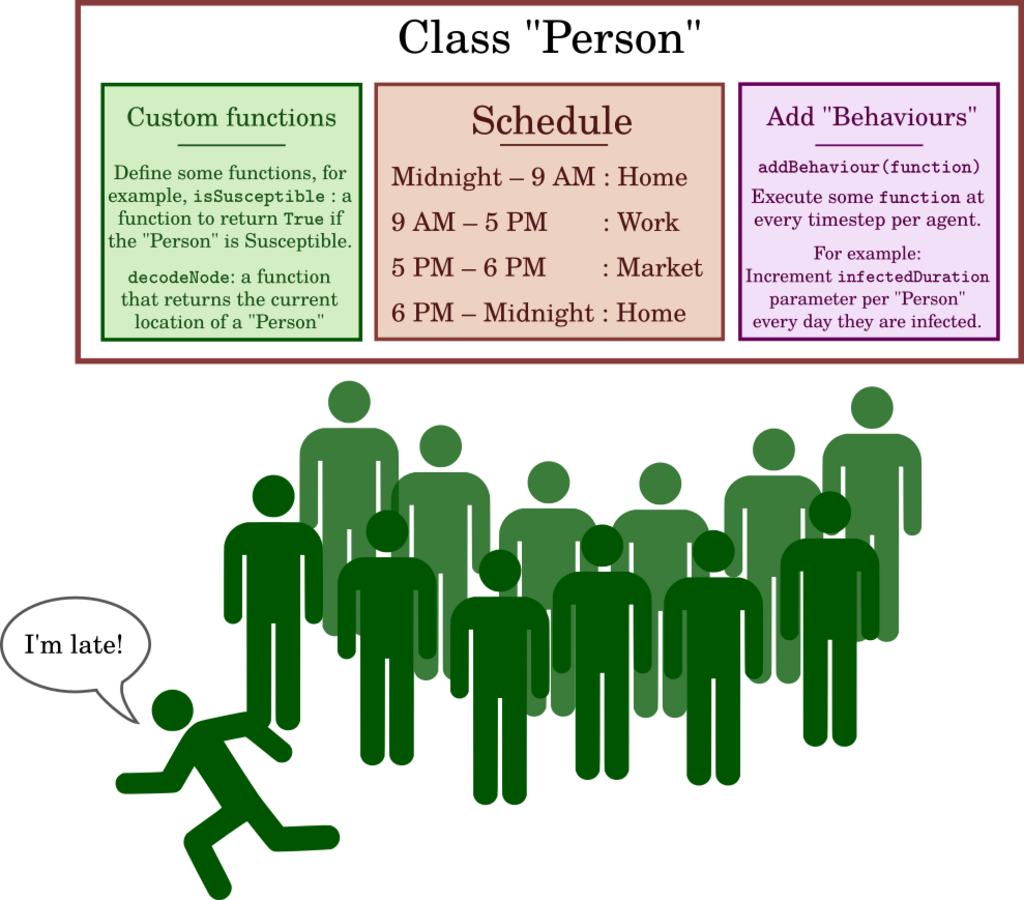

The Agent class can be extended to specify a custom agent in a model with specific attributes. These

could be general attributes like HHID, WorkplaceID, Age or Gender. One could also define model-specific attributes like vaccinationStatus which could, for example, record whether or not an agent was vaccinated, or even a relativeSusceptibility which determines the relative susceptibility the individual has to being infected. A pre-defined extension of the Agent class is the StatefulAgent class, which endows the Agent with a Finite-State Machine, allowing them to be in one -- and only one -- disease state at any given time. One could further define include actions that must be performed by agents whenever they enter or exit these states, as well as actions that are performed in every simulation tick.

In addition, certain abstract and highly-used concepts have been highlighted and defined using the framework's language, like schedules that govern the movement of individuals, and behaviours which are actions that are performed by every agent at every time-step.

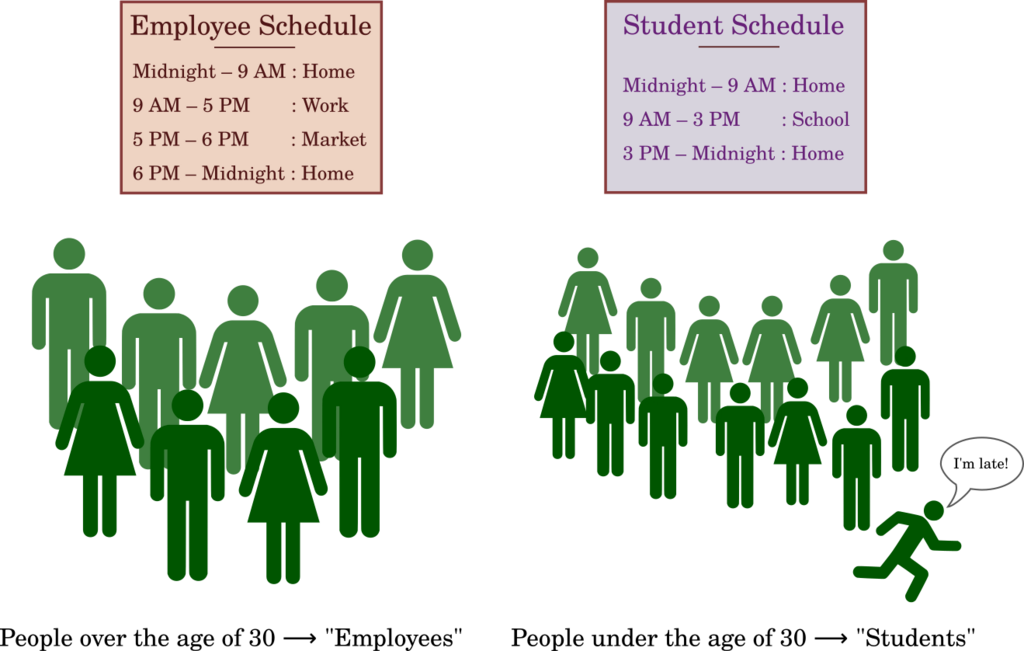

Schedules

Every individual agent follows a schedule that is defined by the modeller. Such schedules specify agent locations across time. These schedules can be dynamic, can depend on the current state of the agent, and can be affected by interventions that are imposed. For example, one could define different schedules for individuals depending on whether they are above the age of 20 or below it. In the former case, these individuals could be considered as “employees”, who go from home to work, while in the latter case, they could be “students” who go from home to school. These conditions can be made as general or specific as necessary.

For example, one could define a schedule for all agents who happen to be symptomatic, which involves them spending more time at home rather than at work or school, thereby exploring the effect of “quarantining” symptomatic individuals. Thus, complicated network structures can be modelled by incorporating granularity into the schedules of different individuals.

Behaviours

A behaviour is an action that is performed by each agent at every time-step, and can be defined within the

user-defined extension of the Agent class using the framework-defined addBehaviour

function. These behaviours can be used to model (for example) whether or not an individual will go to a vaccination

centre to get vaccinated, or alternatively to count the number of days that an individual has spent in the infected

compartment. Such behaviours thus give the modeller the flexibility to perform a repetitive task per agent per

time-step.

Interventions

A modeller could further define a set of externally defined rules imposed on the agents. Such “interventions” could represent scenarios such as lockdowns or vaccination drives. BharatSim allows for the incorporation of such interventions in order to study a range of counterfactual scenarios. Multiple types of interventions can be incorporated, with different activation, deactivation, and reactivation conditions over the course of the simulation.

In the engine, an Intervention is a small, named piece of logic that the simulation checks on every

tick. Each intervention defines (i) a unique name, (ii) a predicate for when it should become active

(shouldActivate) and when it should stop being active (shouldDeactivate), and (iii) two

optional hooks: firstTimeAction (run once at activation) and whenActiveAction (run on

every tick while active). This makes interventions a natural place to encode policy changes (e.g. “close schools at

tick 50”) or counterfactual scenarios (e.g. “apply a vaccination campaign for 30 ticks”) without entangling that

logic with agent behaviours. Active interventions are exposed through the simulation Context, which

makes it possible for other model logic to react to “what is currently in effect”.

BharatSim provides a few convenient intervention flavours. The generic factory

Intervention lets a modeller supply activation/deactivation functions directly. If an intervention

needs a fixed calendar window, IntervalBasedIntervention activates at a specified start tick

and deactivates at an end tick. If the end time should be expressed relative to when the intervention

starts, OffsetBasedIntervention activates when a user-defined condition becomes true and then

deactivates after n ticks from its start (it records the start tick internally). Finally,

SingleInvocationIntervention is useful for one-off events (e.g. a single announcement or seeding step):

once it has fired, it will never activate again. Internally, the engine maintains sets of inactive and active

interventions and updates them as the simulation progresses.

A typical modeller's workflow

A typical modeller's workflow while using BharatSim to answer a question is shown below.

First, they would select the geographic region and demographic resolution required for their study, and using the synthetic population pipeline described in the section on generating a synthetic population, they would create a population for their simulations.

Next, they would use BharatSim's domain specific language to extend agents, states, networks, and behaviours to create their own, arbitrarily complex, model. The model can then further be refined by specifying policy-level interventions, like lockdowns, vaccination drives, or different testing strategies. The modeller can configure and run multiple simulations, and evaluate counterfactual interventions. The resulting output can then be analysed in the visualisation engine to explore temporal and spatial patterns, compare counterfactual scenarios, and draw conclusions relevant to epidemiological dynamics or policy decisions.

Future work and extensions

While BharatSim was initially conceived in the context of epidemiological modelling, we believe it can have uses in a variety of different fields where large, heterogeneous populations and their interactions play a central role. Its ability to represent individuals, households, and institutions within a statistically grounded, spatially explicit synthetic population makes it well suited to studying social, economic, and behavioural processes beyond disease spread. In particular, in the social sciences, computational simulations offer a way to move beyond the simplifying assumptions of economic and game-theoretic models. BharatSim could thus enable social scientists to study how large, heterogeneous populations respond to policies and institutional arrangements, and how collective outcomes emerge from individual interactions, using a realistic representation of an Indian population.